Last month, Mary-Jayne Rust introduced the idea of The Great Turning, the turn towards life-enhancing structures and the world view which sees the web of life as sacred and humans embedded within it. This Digest continues that theme.

The Great Turning is appearing in many forms. I am not suggesting this will ‘save’ us – for we all know The Great Unravelling has much further to go. Yet while we grieve the desecration of our planet, while we try to resist business-as-usual, we can also restore and re-imagine our relationship with the more-than-human world, our kin, wherever we can. The vital work of repairing relationships can continue to the end of life. Here are a few examples of the ways in which this is happening.

Re-Wilding has become part of mainstream thinking. At the core of this vision is trust in the intelligence of wild nature: she has her own order, she can heal herself when given the right conditions. This counters our centuries-old view that nature must conform to human order, to be ruled under our laws. One example, well known in the UK, is the re-wilding of the 3,500 acre Knepp Estate near London which is seeing extraordinary increases in wildlife. Extremely rare species such as turtle doves, nightingales, peregrine falcons and purple emperor butterflies are now breeding there. In her book Wilding: The Return of Nature to a British Farm Isabella Tree describes the resistance they met from some of their local community to their proposals for Knepp in the early days. The idea of not farming their estate was seen as “an affront to the efforts of every self-respecting farmer, an immoral waste of land, an assault on Britishness itself”1. Perhaps these entrenched views are beginning to shift?

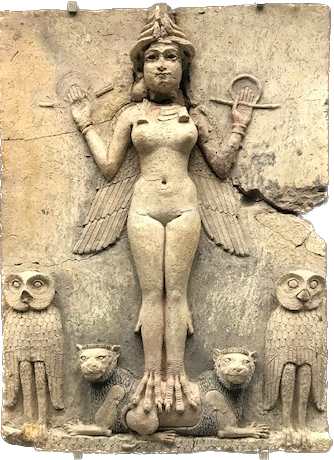

The question “What does it mean to re-wild humans?” has also caught the popular imagination, reminding us we are animals. The popular view of our animal nature is portrayed by the famous case of Dr Jekyll who turns into Mr Hyde, a murderous werewolf, by night. At the same time children’s stories are filled with friendly animals who talk, some half human, half animal. In His Dark Materials, a recent trilogy by Phillip Pullman, every human has an animal daemon, a physical manifestation of the soul, showing our animal nature as a vital source of energy, guidance and wisdom. But children are being stolen and severed from their daemons, mirroring our loss of connection with our creatureliness in modern society. Is there a turn towards recognising the gifts of our animal nature? This terracotta tablet is a reminder of how our ancestors honoured it. Divine Lady Owl is in the British Museum, dated between 1800-1750 BCE, possibly from Ancient Mesopotamia, now Iraq.

Author's photo

Research over past decades shows the sentience and intelligence of animals. Primatologist Jane Goodall has devoted her life to studying the social life of chimpanzees. Wherever she speaks in the world she brings stories of relationship: a mix of extraordinary stories about chimps in the wild – as well as tragic stories of chimps kept in captivity for medical experiments. She is one of an increasing number of people who bring emotional intelligence into the world of science. One outcome of this work is that animals are now recognised as sentient in UK domestic law.

Some recognise our kin as teachers. In the film My Octopus Teacher, Craig Foster enters into the world of the octopus, forming an unlikely relationship with this creature, from whom he learns: how to feel part of a place rather than a visitor; how to be sensitive to ‘The Other’; how to foster trust and feel empathy - when she was wounded he also felt wounded. After this transformative experience, from burn-out to love, Foster set up the Sea Change Project to take care of the underwater sea forests of South Africa. This is a great example of reciprocity in action.

A range of books published on plant relationships and sentience has appeared in recent decades. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants by Robin Wall Kimmerer describes the many ways in which plants can be our teachers. Her writing is a mix of botany, story-telling and personal experience as part of the Native American Potawatomi tribe. She writes, “In the teachings of my Potawatomi ancestors, responsibilities and gifts are understood as two sides of the same coin. The possession of a gift is coupled with a duty to use it for the benefit of all. A thrush is given the gift of song—and so has a responsibility to greet the day with music. Salmon have the gift of travel, so they accept the duty of carrying food upriver. So when we ask ourselves, what is our responsibility to the Earth, we are also asking, “What is our gift?” She reminds us that “reciprocity - returning the gift - is not just good manners; it is how the biophysical world works”2.

In Finding the Mother Tree Suzanne Simard tells us that trees are social creatures who communicate with each other in cooperative ways. Her research has shown how trees can share nutrients at critical times to keep each other healthy. For example, the mother or hub tree can recognise her own kin and will send more nutrients to her kin than to other saplings

.

Author's photo

Both these books are bestsellers. Both authors make a bridge between the world of science with a more ensouled way of seeing and indigenous worldviews, a vital act of holding together seeming opposites.

There is a growing indigenous-led movement to recognise the Rights of Nature. For example, in 2008 Ecuador became the first country to recognize Rights of Nature in its Constitution. In March 2017 New Zealand granted rights of personhood to the Whanganui River. These examples, along with many others, show an important step in the turn from anthropocentric law, which views nature as property, to recognising the rights of ecosystems and species, similar to the concept of fundamental human rights. A recent documentary The Rights of Nature discusses the complexities of putting this into practice and includes how this functions in the urban setting of Santa Monica, California

Research now confirms what indigenous peoples have been telling us for centuries: the earth is alive. The more we learn about the diverse intelligences of our kin the more we learn about ourselves as animals. These stories, and so many more, show the turn from a human-centred worldview towards one which recognises we are part of the web of life; we have a role to play. What are our gifts?

Mary-Jayne Rust is an ecopsychotherapist, Jungian Analyst and art therapist. Alongside her therapy practice she teaches ecopsychology, a growing field of inquiry into our complex relationship with the earth, our home. Her publications include Towards an Ecopsychotherapy, Confer Books 2020. She grew up beside the sea and is wild about swimming. Website link. www.mjrust.net

Footnotes

- Isabella Tree (2018) Wilding: The Return of Nature to a British Farm. p.98.

- Robin Wall-Kimmerer Returning the Gift